Triple Crisis: Earth - Energy - Money

Peaked Energy and Climate Chaos: two aspects of overshoot

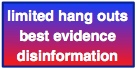

- Blind Men & Elephant

- Peak & Climate together

- can't burn fuel that does not exist

- cut energy by 2050?

- Future Scenarios: a permaculture perspective

- Peak Experts: interconnections

- most eco groups ignored Peak

- Triple Crisis - DC - Sept. 14-16, 2007

(The underlying "Blind Men and the Elephant" image came from this Word Info site)

(The underlying "Blind Men and the Elephant" image came from this Word Info site) |

Peak Oil and Climate Change resemble the parable of the blind men touching an elephant. Each observer is correctly describing what a part of the elephant is, but none have a holistic understanding.

Peak Oil and Climate Change are two facets of the problem of overshoot, and neither can be mitigated in isolation from the other.

"I realized that one of the best use of the US Energy Policy History work may be to convince environmentalists and others that think peak oil is a scare tactic or financial manipulation, that it is in fact a real problem - not something that just popped up, it has been recognized as a problem for decades, and that access to the energy resources of other countries is the main reason that we have been able to ignore it for so long. The intention would be of course to connect the movements so that all can see the elephant for what it is."

-- David Room, Coordinator, Local Clean Energy Alliance

The Most Important Question

The most important question facing the human race is how we respond to the interconnected crises of Peaked Oil, Climate Chaos, overpopulation, and resource conflicts. These crises resemble the parable of the blind men touching an elephant. Each observer is correctly describing what a part of the elephant is, but none have a holistic understanding. Peak Oil and Climate Change are two facets of the problem of overshoot, and neither can be mitigated without the other.

The global crises of the end of cheap oil and the start of climate change require global levels of solutions -- we need to relocalize everywhere.

We are not merely at peak oil, we are at peak technology, peak money, peak communication, and peak everything else. Real solutions would require us to redirect the energy, talents, resources of global capitalism, the military industrial complex, universities, media and other pillars of our society.

We have enough resources and talent to shift civilization to create a peaceful world that might be able to gracefully cope with the end of concentrated fossil fuels, or to create a global police state to control populations as the resources decline. The "War on Terror" is actually a long planned World War to control finite fossil fuels that power civilization.

Understanding why civilization did not respond to the warnings of resource depletion decades ago is needed if a shift toward sanity is still possible at this late date. This is a simple question that has a complicated answer - since these decisions were not made democratically. Addressing Peak and Climate would require world peace instead of Peak Oil Wars.

We are not "addicted" to oil -- the modern world is completely dependent upon fossil fuels for industrial agriculture systems, transportation networks, and the growth based monetary system. Addictions are things you can give up -- but oil runs our civilization.

Trying to mitigate Peak Oil and Climate Chaos separately makes both worse.

Peak Oil and Climate Change can only be addressed in combination, trying to tackle one without the other is a proven failure.

Focusing solely on oil depletion leads to destructive policies aimed at increasing liquid fuels production -- “alternative” fuels that can have worse environmental impacts than conventional petroleum, including accelerated climate change. Efforts to deal with Peak without Climate awareness led to the false solutions of tar sands, offshore drilling, Liquid Natural Gas, Shale Gas, mountaintop removal, and nuclear power.

Focusing on Climate Change while ignoring energy limits is one of the reasons for the political backlash against climate change awareness. Efforts to deal with Climate without Peak fail to understand what is happening, and rarely consider how dependent our food system is on concentrated fossil fuels. Most of the climate movement frames these concerns as we should reduce energy consumption instead of we will reduce consumption because you cannot burn fuel that does not exist. Framing the question as how we will use the remaining oil avoids the problem of climate change denial.

David Holmgren, the co-orginator of Permaculture, is author of Future Scenarios, about the interconnections between Peak Oil and Climate Change - online at www.futurescenarios.org

Holmgren says that "Economic recession is the only proven mechanism for a rapid reduction of greenhouse gas emissions ... most of the proposals for mitigation from Kyoto to the feverish efforts to construct post Kyoto solutions have been framed in ignorance of Peak Oil. As Richard Heinberg has argued recently, proposals to cap carbon emissions annually, and allowing them to be traded, rely on the rights to pollute being scarce relative to the availability of the fuel. Actual scarcity of fuel may make such schemes irrelevant."

Involuntary Simplicity: We Cannot Burn Fuel That Does Not Exist

"A hungry man is an angry man."

-- Bob Marley, "Them Belly Full (But We Hungry)""We do need to cut global carbon dioxide emissions by at least the 50% to 70% recommended by the United Nation Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. The Bush administration understands that this means the end of economic prosperity and industrial civilization as we know it. That is why Bush refuses to even acknowledge that global warming exists."

-- Dale Allen Pfeiffer, From the Wilderness

Concern about melting glaciers and extinction of charismatic megafauna is less likely to influence governmental energy policies than desperate scrambles to replace depleting fossil energy supplies.

Most projections of future greenhouse gas levels ignore the fact that fossil fuels are finite. Focusing solely on climate change ignores the most important question facing humanity -- whether to "spend" the remaining oil on solar panels or battleships (a simplified version of the choice).

This is the way that carbon emissions are going to be reduced, not through voluntary simplicity nor offset campaigns.

If Peaked Energy results in severe hardships -- massive unemployment, a financial crash, food shortages, transportation disruptions -- it will be difficult to convince many people that we need to leave the oil, natural gas and coal in the ground to keep planet Earth stable enough to support human civilization. Framing the energy crisis as a decision about how to use the remaining oil can shift the debate toward more productive discussions: solar panels or battleships, relocalizing production or globalization, high speed trains or NAFTA Superhighways, boosting local businesses or subsidizing Wal-Mart big boxes. Each of these decisions is a choice whether to address the end of cheap oil and the start of climate change through accelerated business as usual or whether we will shift toward more sustainable behaviors. Unfortunately, these decisions are made by small elites that became wealthy and powerful through the destructive practices, and shifting course would be an admission that they screwed up.

Cut Greenhouse Gases by 2050?

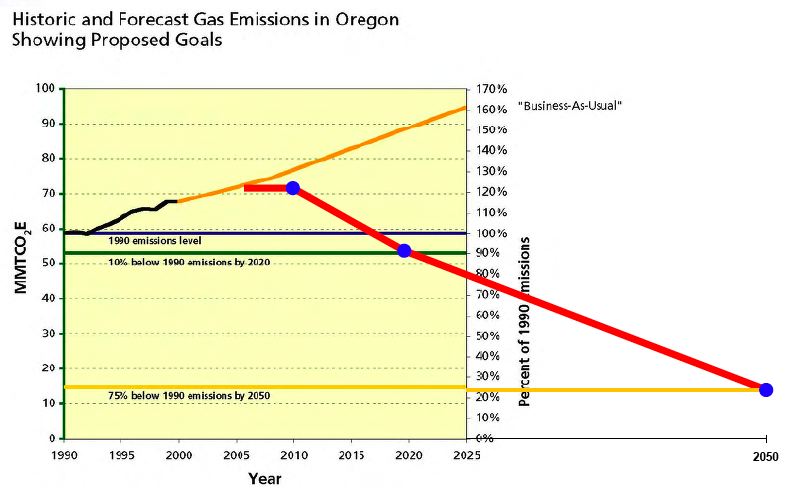

A chart from the Oregon Department of Transportation showing a proposal for a steep reduction in greenhouse gas emissions over the next several decades looks remarkably similar to the famous Hubbert Curve of oil depletion.

The black line mostly represents the increases during the Clinton - Gore administration. The Yellow line is the Bush 43 regime, plus projections of continued growth of fossil fuel combustion. The red line shows the official promises to stabilize carbon emissions and then reduce them over the next half-century (to 75% of 1990 emissions by the year 2050).

The widespread fixation in the environmental movement to look at climate change while ignoring Peak Oil suggests that some forces who fund some environmental groups decided the way to subtly suggest "Peak Oil" to environmentalists is to focus on the "2050" goal as a way to get people used to the idea that the oil age will be over in a few decades.

"Awareness of Climate Change by the media and general public is obviously running well ahead of awareness about Peak Oil, but there are interesting differences in this general pattern when we look more closely at those involved in the money and energy industries. Many of those involved in money and markets have begun to rally around Climate Change as an urgent problem that can be turned into another opportunity for economic growth (of a green economy). These same people have tended to resist even using the term Peak Oil, let alone acknowledging its imminent occurrence. Perhaps this denial comes from an intuitive understanding that once markets understand that future growth is not possible, then it's game over for our fiat system of debt-based money."

-- David Holmgren, co-originator of permaculture, "Money vs. Fossil energy: the battle to control the world" www.holmgren.com.au/DLFiles/PDFs/Money_vs_Fossil_Energy.pdf

www.futurescenarios.org David Holmgren, "Future Scenarios: Mapping the cultural implications of peak oil and climate change"

Peak Experts on the Interconnections

The western Governments and their financial advisors probably continue to live in the past, imagining a temporary downturn that reacts to traditional medicine such as the issue of new liquidity to stimulate consumerism, when what they may face is the Second Great Depression. Apparently many financial and political elements foresaw the arrival of the First Great Depression in 1929 but could not act for fear of being held responsible for it. These psychological factors may explain why governments appear to find it easier to react to the perceived threats of climate change than face the raw reality of declining energy supply.

-- Colin Campbell, February 2008 issue of ASPO Ireland

www.aspo-ireland.org/contentFiles/newsletterPDFs/newsletter86_200802.pdf“Peak Oil and Climate Change are a bigger threat together than either are alone. Peak Oil and Climate Change must be fused as issues – an approach is needed to deal with them as a package.”

“The confluence of Peak Oil and Climate Change means that it is now time to ask ourselves, as a species, the biggest questions we can. So let’s ask those questions now. What do we want to achieve with our remaining oil (and gas) resources? What do we want our legacy to be? What are we aiming towards as a species and does that meet what we want to achieve as individuals? How do we want to achieve this? Do we want to make the transition as easy as possible? Do we eschew personal responsibility and have blind faith that ‘the markets’ or ‘technology’ will solve everything, thus putting off doing anything? It simply does not make sense to expand the use of energy resources that will increase Climate Change if our ability to deal with those magnified consequences will be even more depleted further down the road.”

-- James Howard Kunstler

www.kunstler.com/mags_diary23.html

April 28, 2008

Belief System

A friend asked me how come the public apparently grasps the reality of climate change but can’t seem to wrap its collective brain around the unfolding oil crisis.

I'm not convinced that the public does grasp climate change. It's perceived, perhaps, as a background story to daily life, which goes on regardless. Are you even sure Hollywood didn't invent it -- and maybe some boob at Time Magazine is selling it as though it were really happening?

Few have anything to gain by espousing denial of climate change. It's hard for most people to tell if they have been affected by it. It doesn't quite seem real. Those who actually make gestures in the face of it –- screwing in compact fluorescent lightbulbs, buying Prius cars -- end up appearing ridiculous, like an old granny telling you to fetch your raincoat and rubbers because a force five hurricane is organizing itself offshore, beyond the horizon.

The public appears aggressively clueless about the peak oil story. They do not accept any threats to the motoring regime. The news media is surely not helping sort things out. I saw a remarkable display of ignorance on CNN last week when the new resident idiot-maniac Glenn Beck hosted Teamster Union boss James Hoffa and they agreed that the oil companies were to blame for high fuel prices. To put it as plainly as possible, Beck doesn't know what the fuck he's talking about, and it's disgraceful that CNN gives free reign to this moron to misinform the public. It's perhaps equally amazing that Hoffa doesn't know we have entered a permanent global oil crisis based on demand having outrun supply. These two idiots think that if Exxon-Mobil built a new refinery down in Louisiana, everything would be fine, diesel fuel would go back down to 99 cents a gallon, and it would be Christmas every morning.

www.energybulletin.net/36739.html

Published on 4 Nov 2007 by Museletter / Global Public Media. Archived on 4 Nov 2007.

Big melt meets big empty: Rethinking the implications of climate change and peak oil

by Richard Heinberg

www.energybulletin.net/24529.html

Published on 9 Jan 2007 by Energy Bulletin. Archived on 9 Jan 2007.

Bridging Peak Oil and Climate Change Activism

by Richard Heinberg

The problems of Climate Change and Peak Oil both result from societal dependence on fossil fuels. But just how the impacts of these two problems relate to one another, and how policies to address them should differ or overlap, are questions that have so far not been adequately discussed.

www.richardheinberg.com/museLetter/196

# 196: Coal and Climate

MuseLetter 196/August, 2008

by Richard Heinberg

(This month's essay is another chapter from the retitled book-in-progress, BLACKOUT: Coal, Climate and the Last Energy Crisis.)

.... relying on fossil fuel depletion to safeguard the world's climate would entail a serious risk: What if the new lower estimates of coal reserves turn out to be wrong? Clearly, the world's oil and coal reserves are a mere fraction of total resources. If somehow a way were found to transform a significant portion of remaining resources into reserves, this could entail a significant increase in atmospheric carbon emissions.

This risk also extends to unconventional fossil fuels such as tar sands, shale oil, and methane hydrates. While the potential for the development of these resources is often overstated, since current technology will permit only a very slow extraction rate for tar sands and perhaps no commercial extraction at all of oil shale and methane hydrates, nevertheless there is always the possibility that new technologies will enable their exploitation on a wide scale. Without a stringent emissions policy in place, the consequences for the global climate would be profound.

In general, human society faces a conundrum: unless non-fossil sources of energy are developed quickly, or unless society finds a way to operate with much less energy, and preferably both, the depletion of higher-quality fuels (natural gas and oil) will mean that efforts to obtain more energy will entail burning ever dirtier fuels, and doing so in proportionally larger quantities in order to derive equivalent amounts of energy.

Therefore, to the question, "Will coal, oil, and gas depletion solve Climate Change?", the answer is an unequivocal no. ....

... will climate concerns succeed in driving policy in the face of energy scarcity? Currently, global coal consumption is still growing—faster by volume, indeed, than the consumption of any other energy resource. Can nations experiencing shortages of oil and battered by high energy prices be persuaded to forgo the still relatively cheap energy from coal in order to avert environmental consequences for future generations? ....

The relevance for Climate Change—and other environmental issues, such as resource depletion—is clear: we tend to discount future costs (such as the impact of melting glaciers) just as we do future profits. Thus, asking society to endure present pain in order to avert more widespread suffering in the future is problematic. The present pain must be minor, and the future suffering profound and credible and not too many years distant, in order to persuade us to take an action that we will find uncomfortable or unpleasant.

In the early years of the decade, as the global economy was booming, policy makers in many nations gave considerable attention to Climate Change. Heads of state conferred, strategies were debated, and agreements were forged. Today, as energy scarcity cripples national economies with pain that is both palpable and growing, there is likely to be a greater tendency to discount the future costs of Climate Change in favor of satisfying immediate demand for fuel, no matter how carbon-intensive it may be. There is abundant evidence that this is indeed occurring.

In Europe, while top climate experts offer ever-shriller warnings about the effects of carbon emissions, Italy is planning to increase its reliance on coal from 14 percent of total energy to 33 percent. Throughout the continent, about 50 new coal-fired power stations are being planned for the next five years. The driver for this new coal boom is unequivocally clear: higher natural gas prices. In Germany, 27 new coal plants are planned by 2020, many fueled by lignite—which can produce a ton of carbon emissions for every ton of coal burned.

In the US, despite the cancellation of so many new coal plants in recent years, the National Mining Association projects that about 54 percent of the nation's electric power will be coal-fired by 2030, up from the current 48 percent.

Depletion defeats climate policy in other ways. Carbon taxes become a harder policy to sell as energy prices climb; coal cutbacks are more difficult to make when natural gas is getting more expensive and electricity grids are browning out; and using coal to make liquid fuels starts to look attractive as diesel prices escalate.

Will efforts to address Climate Change solve the economic problems arising from coal, oil, and gas depletion and increasing scarcity? It is possible in principle, but in reality the stronger likelihood is that energy scarcity will rivet the attention of policy makers and private citizens alike because it is an immediate and unavoidable crisis. The result: as scarcity deepens, support for climate policy may fade even as climate impacts worsen.

A Combined Approach

Clearly, the world needs energy policies that successfully address both Climate Change and fuel scarcity. Such policies are likely to be devised and implemented only if both crises are acknowledged and taken into account in a strategically sensible way.

If policy makers focus only on one of these problems, some of the strategies they are likely to promote could simply exacerbate the other crisis. For example, some actions that might help reduce the impact of Peak Oil—such as exploitation of tar sands or oil shale, or the conversion of coal to a liquid fuel—will result in an increase in carbon emissions. On the other hand, some actions aimed to help reduce carbon emissions—such as carbon sequestration or carbon taxes—will make energy more expensive, which, in a situation of energy scarcity and high prices, may be politically problematic and therefore a waste of climate activists' and policy makers' limited resources.

However, many policies will help with both problems—including any effort to develop renewable energy sources or to reduce energy consumption.

For strategic purposes, it is important to understand our human tendency to discount future problems. We must assess which threats will come soonest, and make sure that our sometimes frantic efforts to respond to these immediate necessities do not exacerbate problems that will show up later. Peak oil is clearly the most immediate energy and resource threat that policy makers must deal with. Peak Coal and Climate Change may seem comparatively distant. But all must be taken seriously if we are to do any better than merely to lurch from crisis to crisis, with each new one worse than the last.

If energy scarcity forces policy changes before climate fears can do so, then perhaps world leaders will find that it makes more sense to ration fuels themselves by quota, rather than the emissions they produce. In any case, it will help everyone concerned to have a clear idea of the ultimate extent of coal, oil, and natural gas reserves and future production, as well as a realistic understanding of climate sensitivity and hence the environmental and economic costs of continuing to burn fossil fuels even in depletion-constrained amounts. Otherwise, the policies pursued may simply waste precious time and investment capital while actually making matters worse.

Commentary: Reaping Whirlwinds: Peak Oil and Climate Change in the New Political Climate

By Sharon Astyk (Note: Commentaries do not necessarily represent the ASPO-USA position.)

Political prognostication is a dangerous game, but one of the certainties of the latest election was that the US will not be enacting any significant federal climate legislation. One could be forgiven for wondering what the election has to do with anything. In the two years previously during which the Democrats controlled Presidency, House and Senate, the US had failed also to enact any climate legislation, but we have moved from the faintest possible hope to none at all.

If inaction is certain on climate change, it may be that all is not entirely hopeless if we reframe the terms to addressing our carbon problem. Peak-oil activism could accomplish many of the goals of climate activists. Unlike climate change, peak oil doesn’t carry the ideological associations with the left that climate change does. Could peak oil provide a framing narrative for political action to address both climate change and peak oil? Certainly, a great deal would have to happen in order to accomplish this. But peak oil is a sufficiently powerful and pressing issue that its profile could be raised, particularly if current climate activists were willing to change their focus from the means of achieving consensus on climate change to the end of achieving emissions reductions.

I should emphasize that my subject is the political framing of these issues and that I take the scientific case for Anthropogenic Global Warming (AGW) to be more than sufficient. The question in front of us is not, ―Is global warming real?‖ since the scientific literature is overwhelmingly clear on this point, but rather, ―What is the most effective way to formulate our relationship to climate change so that the greatest good is accomplished?‖

What might be necessary to craft a unified narrative that could get widespread and bi-partisan political support in the US that would serve the interests of everyone concerned with how we burn carbon? Peak oil has been called ―the liberal left-behind movement;‖ but that doesn’t change the fact that peak oil is a bi-partisan concern. Roscoe Bartlett, R–Maryland, has been peak oil’s face in the House. The US military has been a leader in articulating the dangers of peak oil. Peak-oil discussions draw a fascinating and unusual range of participants, across political lines, and it is hard to overstate how uncommon and valuable such an issue is in our highly politically–stratified society. Given the stakes of both issues, this is ground we must build on.

The first requirement is that climate and energy activists need to understand each other better. While there are many important exceptions to my generalities here about the differences between the two communities, in many cases, we do not know each other’s data or political landscape well enough to collaborate well. For example, most climate activists persist in using IPCC figures that imply that far more coal, oil and natural gas will be available in the future than the evidence supports. Meanwhile, some strains of the peak-oil community argue that these resource limits will be sufficient to restrain the worst outcomes of AGW. They fail to grasp that the increases in our understanding of climate sensitivity documented by among others the IPCC update ―The Copenhagen Diagnosis‖ mean that we do, unfortunately, have far too many fossil fuels to be saved by our resource limits.

Second, we need to fully articulate our common ground, and be prepared to compromise in the creation of a shared narrative. The climate-change story is one, broadly, in which we must constrain use of abundant resources voluntarily and consciously. Peak oil’s narrative shifts the emphasis: involuntary constraints will be thrust upon us. The former presumes we must also use our abundant resources to buffer the assaults of an increasingly unstable planet. The latter presumes that we will suffer primarily from failures of built infrastructure.

It is perhaps understandable, then, for those who view climate change as the primary problem to imagine that we can manufacture limitless renewable technologies to mitigate the effects of climate instability. Climate activists generally focus on optimistic predictions for renewable production, often ignore critical technical differences like EROEI, and generally imagine a world of economic growth, therefore understating the economic costs of addressing our future problems.

It is not entirely clear to most of us what life in an unstable climate will look like. On the other hand, it is easy to envision failures of access to gasoline, heating fuel, blackouts. Peak-oil activists tend to gravitate more heavily towards personal solutions, and because infrastructure failure strikes us so viscerally, in some cases, tend to dismiss the possibilities of political responses. Because peak oil has historically been marginalized politically, there is often an assumption that this marginalization cannot be overcome.

In order to accomplish change of the magnitude necessary to respond to each issue, both sides would have to come to terms with one another. Climate change activists have invested a great deal of their narrative in telling people that the new green economy will have plenty of jobs and comparatively low economic costs. Acknowledging that we lack the energy resources to maintain perpetual economic growth requires them to shift their narrative to one of sacrifice for the greater good; this is a much tougher row to hoe, but ultimately, the only viable choice. The strategic emphasis and a new understanding of net energy will have to be on conservation strategies and changing the industrial way of life towards one that is vastly less energy intensive.

The peak-oil community will have to give up its habit of dismissing the political process entirely, and its underlying assumption that no one is going to listen to it. This sounds easy, but may not be. Both parties may have to come to terms with the fact that the most important political responses may not be about renewable build outs, but about basic social protections of ordinary people made vulnerable by both crises.

Peak-oil activists will have to fully come to terms with the reality of adaptation in an unstable climate. Relocalization is a viable tool in our box, and an important one, but simply may not be achievable for many communities that will be disrupted and rendered uninhabitable by climate change. More than a billion climate refugees are predicted in the coming century; it is unlikely that none of us will be among them. Strategies for localization and energy reduction must take seriously predictions of how livable each place will be.

Finally, and most critically, once we find our common ground, we’ll have to stick with it, and commit to working together. Environmental activism has been almost entirely a thing of the left in the US. Framing the narrative of our carbon crisis in terms of peak energy raises the possibility of bi- partisanship, but only if all the participants can actually work together without demonizing one another. That means putting aside the political fractures that divide us. Asking pro-choice and anti- abortion activists to work together, asking people who feel passionately about gay marriage or economic policy to simply table those issues is an enormous challenge. The rage that the right and left feel towards one another seems to be our birthright, and there are legitimate reasons underlying some of that rage, but we must put it aside.

It is indubitable that if we put these issues aside, we’ll be accused of throwing people under the bus. The only justification for tabling other political issues is this: the stakes are the highest in human history. The only justification for changing narratives to which we are attached, in which we believe fervently is this: that some of us will die if we don’t. The only argument for putting aside our rage and fury is simply this: that our rage and fury will be vastly greater when our children die of diseases we might have prevented, when the floods take our homes, when the food runs scarce. For these stakes, we can do almost anything — and we must.

Sharon Astyk is the author of three books on Peak Oil and Climate Change, a small farmer, and a member of the ASPO- USA board of directors. She also blogs at http://www.scienceblogs.com/casaubonsbook

www.oildepletion.org/roger/Solutions/solutions.htm

All industries will be affected, beginning with air transport and related sectors, including tourism which, taken as a whole, is, surprisingly, the world's biggest employer. Transport in all its forms is also in the front line of risk; massive fuel price increases, and actual interruptions in supply would threaten a breakdown of distribution systems and have economic consequences far in excess of any experienced in the developed economies in modern times. These consequences would include high unemployment and inflation.

Secondly, there are implications for the costs, and perhaps even availability, of food. The food chain is massively hydrocarbon-dependent at every stage: fertilisers, chemicals, equipment, transport and processing. A rise in the price of oil will knock-on immediately to a comparable rise in the price of food. Political and social instability as a consequence cannot be ruled out.

Thirdly, the coming oil shock transforms the climate-change agenda. The Kyoto process has been built on the assumption that oil supplies will not be the constraint that will limit carbon emissions in the future, and that if the latter are to be reduced, this will have to be through deliberate limitations on demand. In this new situation, however, the problem is transformed: reductions in affordable oil may turn out to be faster than the most ambitious targets that have been conceived in the context of climate change. The CO2 implications of reduced conventional oil use, vs. the increased use of gas, non-conventional oils, coal, and perhaps nuclear, need examination.

www.theoildrum.com/node/2239

Noisette on February 2, 2007 - 11:54am

Global warming is a comfortable matter for the public to worry about. Its reported effects tend to be ‘away’ (polar bears scrabbling on ice islets), far off into the future (rising sea level), impenetrable (dying species, new plant and animal life), scientifically disputable as claimed (see de-bunker shills), hard to grasp (so what if the temp rises one degree?), welcomed by many: .. Putin could open up Siberia; cool, no more long lasting ice in the winter on my steps! My heating bill is way down!- and, last but not least, raises the specter of world ‘Gvmt.’ or world legislation / collaboration, which is anathema to many and in any case almost impossible to either understand or imagine managing.

Most people’s daily lives are not impacted at all, the change is extremely gradual, and while in many places noticeable by the individual senses and brain, has a kind of inevitability about it - the Cosmos, Rays, Sunspots, warmer water, CO2, God, horrid humans, Weird Stuff! and only requires, it is thought, that people adapt to changes in the ‘weather’ as they have done for millenia, by growing other crops, moving north or inland, etc. etc. All together, it becomes a vehicle for smug catastrophism - exotic examples are thrilling - Tuvalu under water, wow! But who cares?

Most Environmentalists Ignored Peak Oil

The oil industry is one of the top targets of the environmental movement - especially the part that loves to challenge corporate power and abuses. However, few green groups have prioritized developing an environmental response to Peak Oil. Most of them ignored Peak Oil before the peak, some seem unaware of it, while others believe it is a distraction that gets in the way of their campaigns. It is likely that shortages caused by fossil fuel depletion will cause public desperation that will reduce support for environmental restrictions, a dilemma that does not seem to be anticipated by those who lead these campaigns.

"Peak oil is an irrelevant distraction that frames things in a way that only industry is happy with. If we reach the oil peak soon as many (it seems yourself included) believe then so be it, our job is that much easier. If not - and there are plenty of reasons to believe we won't - chief among them that the oil industry will continue to find new and clever ways to "make" oil (shale, etc.) - if not, well then we damn well better not be putting all of our eggs into that basket. We've gotta stop this industry ASAP before the planet fries - you know that just as well as I. I'm not hanging my strategy on theory - I'm betting on good old fashioned organizing. The big problem with the "Peak oil" argument is that it promotes complacency among activists and the public - why fight when the industry will go down of its own accord anyway?"

-- from a former campaigner for Greenpeace USA, sent to this website in 2003

A newer perspective from a Greenpeace campaigner acknowledges Peak Oil. Note that this Greenpeace person is not in the United States (he is in Vancouver, Canada).

www.greenpeace.org.uk/blog/about/deep-green-peak-oil-changes-everything-20080804

Deep Green: peak oil changes everything

Posted by bex on 4 August 2008.

Here's the latest in the Deep Green column from Rex Weyler - author, journalist, ecologist and long-time Greenpeace trouble-maker. The opinions here are his own.

Here is an rebuttal to the claim Peak Oil is irrelevant to the goal of restricting oil company power:

"If you think this industry is rich and powerful now, wait ‘til the supply is clearly on the wane. At the website www.dieoff.com, you can learn that “in 1995, Petroconsultants published a report for oil industry insiders ($32,000 per copy) titled WORLD OIL SUPPLY 1930-2050 which concludes that world oil (extraction) could peak as soon as the year 2000 and decline to half that level by 2025. Large and permanent increases in oil prices were predicted after the year 2000.”

"Black gold is going to go platinum."

-- Barrie Zwicker, from the 2002 documentary The Great Deception

Triple Crisis conference - Washington, D.C. - September 14 - 16, 2007

"Triple Crisis" was a pathbreaking conference held in Washington, D.C., from September 14 through 16, 2007. It was the first major event sponsored by a prominent US based environmental group that blended together Peak Oil and Climate Change as parts of the same crisis. Several speakers noted that "Triple Crisis" is an understatement since civilization faces many other overlapping problems: species extinction, toxic and nuclear wastes, financial meltdown, mineral depletion, agricultural decline (from many factors), among others.

www.ifg.org/programs/Energy/triple_crisis_av/index.htm

IFG Teach-In: Confronting the Global "Triple Crisis"

"Climate Change, Peak Oil, Global Resource Depletion & Extinction"

September 14th-16th, 2007, Washington, DC

Audio and Video from the Speaker at the IFG Teach-In

Panels - September 14th-16th, 2007

Panel 1 - Dimensions of the Global Triple Crisis

Panel 2 - False Solutions, Part 1 and Part 2

Panel 3 - Views From The South: Direct Impacts From Triple Crisis

Panel 4 - Toward A Global Grand Bargain

Panel 5 - Ingredients Of Systemic Change (1)

Panel 6 - Impacting US Policy

Panel 7 - Ingredients Of Systemic Change (2)

www.energybulletin.net/35458.html

Published on 6 Oct 2007 by EarthWatch Ohio.

Confronting the Triple Crisis

by Thomas J. Quinn

A Washington D.C. teach-in on climate change, peak oil and global resource depletion included a presentation from an Ohio nonprofit organization on how to curtail energy use in housing, transportation and food production. The teach-in, entitled Confronting the Global Triple Crisis—The Problems and The Solutions, featured some 60 speakers from 16 countries and attracted close to 900 people to George Washington University over three days in mid September.

Megan Quinn Bachman, outreach director for The Community Solution in Yellow Springs, Ohio, detailed her nonprofit’s efforts to deal with “converging calamities,” including the coming peak and decline in worldwide oil production which will result in oil shortages and skyrocketing prices. “Community is a vision of the future where we conserve and share scarce local resources rather than deplete, destroy and battle over seemingly abundant distance resources,” Bachman said. “It is a vision where we consume far fewer resources, but have a better life, filled with valued relationships rather than valued possessions.”

Joining Bachman on the podium were authors, academics and activists including, as Bachman pointed out in introducing one panel, some of the “world’s foremost experts on issues of peak oil, gas and coal, local and ecological economics, sustainable lifestyles, community, overconsumption and more.” These included author, environmentalist and global warming activist Bill McKibben; Richard Heinberg, author of The Party’s Over: Oil, War and the Fate of Industrial Societies, and Helena Norbert-Hodge, a pioneer of the worldwide localization movement and author of Bringing the Food Economy Home.

Bachman called for curtailing energy use through retrofitting the existing 90 million residential structures and 5 million commercial buildings in the U.S. She said Community Solution has a number of model housing-retrofit projects underway “as we try to determine what the most effective structural and lifestyle changes are to reducing home energy use.”

In transportation, Community Solution is working on a ride-sharing system it calls “Smart Jitney,” which aims to increase vehicle ridership from 1.5 persons per vehicle to 4-5 with the use of existing vehicles and current cell phone technology. But Bachman said this is a short-term strategy, and in the longer term by “revamping local and regional economies, living, working and shopping in the same area, we’ll be able to utilize the more sustainable options of walking, bicycling and mass transit.”

Bachman also called for less fossil fuel use in food production through more locally grown food, eating less and curtailing energy-intensive meat consumption. She pointed out that two-thirds of the U.S. population is obese or overweight as Americans overconsume food just as they do energy, water and other resources. “When we shift to using fewer fossil fuels, start to repair and rebuild the damaged soil and grow more real food, we’ll need vastly more human labor to do it,” Bachman said. “This includes more full-time farmers for sure, but all of us producing some food is the most efficient, sustainable and secure agriculture.”

And that’s just the kind of plan Community Solution has in mind for Yellow Springs, a town of 3,700 people outside Dayton. The non-profit has land for a model neighborhood community it calls Agraria, which will include small “passive” houses that do not need heating or cooling systems, plus vegetable gardens to provide food for neighbors to share. Agraria would help to produce a web of interdependent social and economic relationships and serve as an educational and cultural center to transform Yellow Springs, Bachman said.

The Agraria plan was developed after Bachman and others with the nonprofit went to Cuba in 2004 to do a documentary, “The Power of Community: How Cuba Survived Peak Oil.” The film details the grass-roots-based urban agricultural revolution and renewable energy movement that swept through this island nation after its oil lifeline, the Soviet Union, collapsed in the early 1990s. “I believe that this is how the change will take place, not from above, but from within,” Bachman said. “From individuals and communities and eventually entire nations pioneering a better way to live on this planet.”

The teach-in, sponsored by the International Forum on Globalization and Institute for Policy Studies, was subtitled, “Powering-Down for the Future—Toward an International Movement for Systemic Change: New Economies of Sustainability, Equity, Sufficiency and Peace.”

CD/DVD recordings of plenary sessions and workshops at the teach-in are available. Go to www.conferencerecording.com and www.ifg.org for more information. For more information about The Community Solution, go to www.communitysolution.org.

“Planning for Hard Times” Conference on Oil Depletion & Climate Change Yellow Springs, OH • October 26 - 28

Join activists, educators and community leaders pioneering a low-energy way of life to lessen the impact on the global climate and dependence on fossil fuels.

To register, go to www.communitysolution.org. For more information call The Community Solution at 937-767-2161 or email info@communitysolution.org.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Editorial Notes ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Journalist Tom Quinn was the moving force behind the groundbreaking series on Peak Oil and energy run by the Cleveland Plain Dealer newspaper, for which they received recognition from the Columbia Journalism Review.

The original article is included in the full October/November issue of "EarthWatch Ohio" which is availble online as PDF.

-BA

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Original article available here.